Your cart is currently empty!

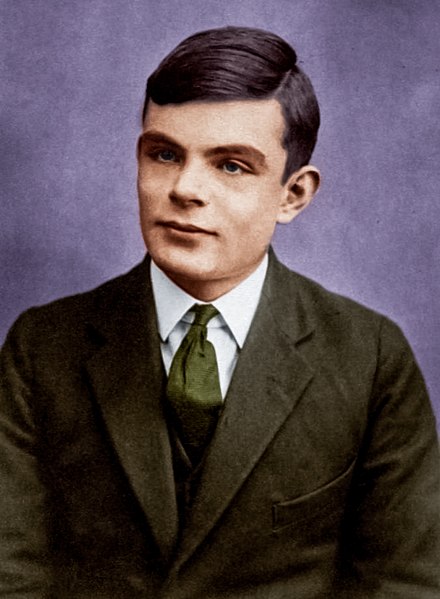

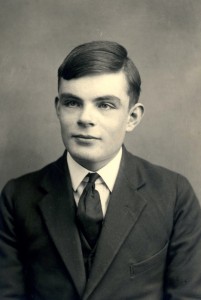

Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (1912–1954) was a British mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. He is widely considered the father of theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence. Turing’s groundbreaking work during World War II in breaking the German Enigma code saved countless lives and significantly shortened the war. However, his remarkable achievements were overshadowed by the tragic consequences of his persecution for being homosexual in a time when homosexuality was criminalized in the United Kingdom.

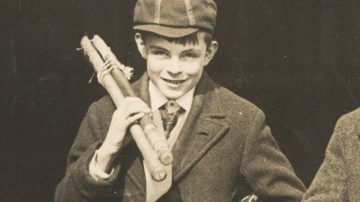

Early Life

Turing was born on June 23, 1912, in Maida Vale, London. His parents, Julius Mathison Turing and Ethel Sara Stoney, had Anglo-Irish roots. Raised in southern England, Turing displayed extraordinary intellectual abilities from an early age. His fascination with science and mathematics flourished despite the lack of encouragement from traditional education systems.

Turing’s first school, St. Michael’s in St. Leonards-on-Sea, recognized his genius early on. Later, at Sherborne School, Turing’s natural inclinations for mathematics and science clashed with the institution’s emphasis on classical education. His headmaster doubted his potential, writing to Turing’s parents, “If he is to stay at public school, he must aim at becoming educated.” Nevertheless, Turing’s brilliance shone through. At just 16, he independently grasped Albert Einstein’s questioning of Newtonian physics.

Academic Journey

Turing attended King’s College, Cambridge, where he earned first-class honors in mathematics. In 1938, he completed his PhD at Princeton University under the supervision of Alonzo Church, where he developed the concept of ordinal logic and introduced the Turing machine, a theoretical model that became a cornerstone of computer science. His dissertation, Systems of Logic Based on Ordinals, laid foundational ideas for what would later become artificial intelligence.

Turing’s fellowship at King’s College was awarded on the strength of his work on the central limit theorem, demonstrating his originality even when earlier proofs of the theorem existed. His method and insights were lauded for their ingenuity.

Contributions During World War II

During World War II, Turing worked at Bletchley Park, the UK’s codebreaking center. His work on deciphering the Enigma machine, particularly through the development of the Bombe, was instrumental in intercepting Nazi communications. These efforts were critical in turning the tide of the war, especially in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Turing’s Banburismus technique applied sequential statistical analysis to reduce the number of possible Enigma settings, making the codebreaking process more efficient. His collaboration with fellow cryptanalysts like Gordon Welchman and Hugh Alexander enhanced these methods. Turing’s ingenuity extended to the secure voice communication system codenamed Delilah, though it was never deployed.

Turing’s LGBT Life

Alan Turing’s sexual orientation profoundly influenced his personal life and legacy, set against the backdrop of a deeply repressive era in British history.

Early Awareness and First Love

Turing’s first known romantic attachment was with Christopher Morcom, a classmate at Sherborne School. Morcom’s untimely death in 1930 deeply affected Turing, intensifying his focus on science and mathematics as a way of coping with his grief. Morcom’s influence remained a guiding light in Turing’s life, inspiring his intellectual pursuits. Turing expressed profound philosophical reflections on mortality and the relationship between the physical and spiritual realms in letters to Morcom’s mother.

Secrecy and Duality

Homosexuality in early 20th-century Britain was criminalized under laws that labeled it “gross indecency.” Consequently, Turing’s sexuality was a closely guarded secret for much of his life. His engagement to Joan Clarke, a fellow mathematician and cryptanalyst, revealed the complexity of his personal relationships. Turing was candid with Clarke about his sexual orientation, leading to a mutual decision to end their engagement while maintaining a lifelong friendship.

Post-War Relationships and Persecution

After the war, Turing began to live more openly, navigating a society hostile to same-sex relationships. In December 1951, Turing met Arnold Murray, a 19-year-old unemployed man. Their relationship led to Turing’s home being burgled by an acquaintance of Murray. Reporting the crime inadvertently exposed Turing’s sexuality to authorities. In 1952, Turing was charged with “gross indecency” under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885.

Faced with imprisonment, Turing chose probation contingent on undergoing chemical castration through hormone therapy. This treatment, which involved synthetic estrogen, caused devastating physical and psychological effects, including impotence and breast tissue development. The conviction stripped Turing of his security clearance and tarnished his reputation, effectively ending his government work.

Turing’s resilience in the face of persecution was evident. He continued his scientific work, including groundbreaking research on morphogenesis, which explained the chemical basis of biological pattern formation.

Legacy and Recognition

Turing’s persecution highlighted the broader injustice faced by LGBTQ+ individuals during this era. In 2009, a public petition led to a government apology, with Prime Minister Gordon Brown acknowledging the “appalling way” Turing was treated. In 2013, Turing received a royal pardon, and the “Alan Turing Law” was introduced in 2017, retroactively pardoning thousands of individuals convicted under historical anti-homosexuality laws.

Contributions to Computing and Artificial Intelligence

Turing’s work extended beyond cryptography. He conceptualized the Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) and laid the groundwork for modern computing. His 1950 paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” introduced the Turing Test, a criterion for machine intelligence that remains influential in the field of artificial intelligence. Turing also designed early chess algorithms, demonstrating his foresight into programming and machine learning.

Tragic Death and Controversy

Turing died on June 7, 1954, from cyanide poisoning at the age of 41. A half-eaten apple found beside his bed led to speculation about whether his death was suicide or an accident. While the coroner’s report ruled it a suicide, alternative theories suggest accidental inhalation of cyanide fumes during a chemical experiment. His mother believed the death was unintentional. Philosophers and biographers have debated whether Turing deliberately left the circumstances ambiguous, shielding his mother from the pain of knowing he may have taken his own life.

Posthumous Recognition

Turing’s contributions are now widely celebrated. In 2019, he was chosen to feature on the UK’s £50 banknote, symbolizing his enduring legacy. Statues, academic institutions, and awards, including the Turing Award, honor his life and work. In 2023, discussions emerged about erecting a statue of Turing on Trafalgar Square’s fourth plinth to commemorate his contributions and resilience.

Legacy in the LGBTQ+ Community

Alan Turing’s life story has become a touchstone in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights. His resilience in the face of systemic discrimination and his monumental contributions to science and society serve as a reminder of the destructive impact of prejudice and the enduring power of human ingenuity. Turing’s name is celebrated at Pride events, and his life is taught in schools as a testament to perseverance and brilliance.

References

- Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Copeland, B. Jack. The Essential Turing. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Leavitt, David. The Man Who Knew Too Much: Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer. Phoenix, 2007.

- “Alan Turing: The Codebreaker Who Saved Millions of Lives,” BBC News, 2012.

- “Royal Pardon for Codebreaker Alan Turing,” BBC News, 2013.

- “Alan Turing Law: Thousands of Gay Men to Be Pardoned,” The Guardian, 2017.

- Turing, Alan. “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” Mind, 1950.

- Mahon, A. P. The History of Hut Eight 1939–1945. National Archives Reference HW 25/2.

- Petzold, Charles. The Annotated Turing: A Guided Tour Through Alan Turing’s Historic Paper on Computability and the Turing Machine

- Bernhardt, Chris. Turing’s Vision: The Birth of Computer Science 2017

- The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park: The Secret Intelligence Station that Helped Defeat the Nazis (2020)

- The Alan Turing Codebreaker’s Puzzle Book (2017)

Leave a Reply