Your cart is currently empty!

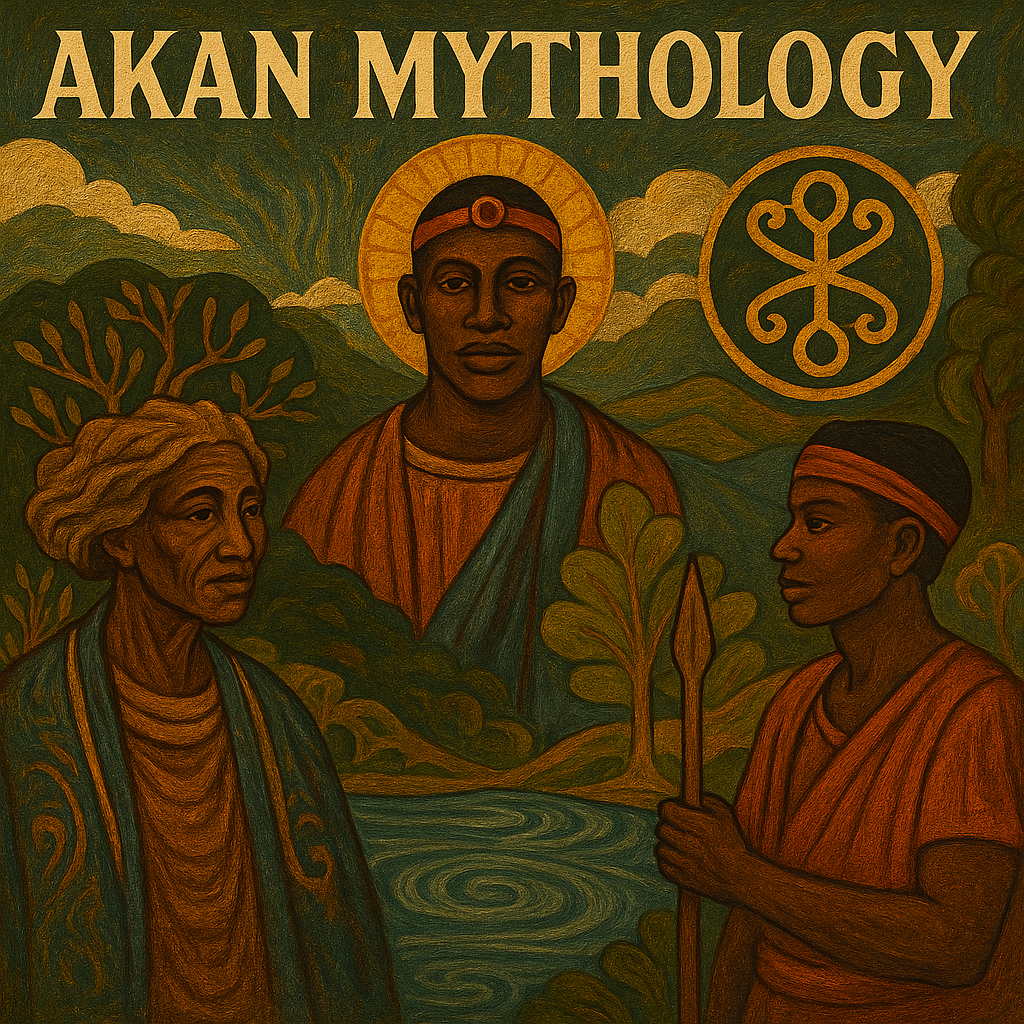

Akan Mythology – The Spiritual Tapestry of the Akan People

Introduction

Akan mythology is a vast and intricate belief system originating from the Akan people of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa. Unlike a singular, unified doctrine, Akan mythology consists of numerous folktales, legends, and deities passed down through generations, shaping the spiritual and cultural identity of the Akan people.

At its core, Akan mythology emphasizes creation, ancestral veneration, and the interconnectedness between the natural and spiritual worlds. The Akan people believe in a supreme deity, Nyame, who governs over all existence. Alongside Nyame exist a host of deities known as the Abosom, each representing various natural and cosmic forces.

Core Beliefs & Themes in Akan Mythology

- Creation and Cosmology – Nyame, the supreme god, is the creator of the universe. His divine authority extends over all things, with his consort Asase Yaa representing Earth and fertility.

- The Spirit Realm – The Akan recognize the Asaman, the realm of the spirits, where ancestral souls and divine beings reside.

- Ancestral Veneration – The Akan people hold their ancestors in the highest regard, believing they continue to influence the living world. Rituals, libations, and ceremonies maintain their favor.

- Moral Lessons & Trickery – Mythology features trickster figures like Anansi the Spider, who embodies wit and survival in the face of adversity. His tales spread across the African diaspora.

- Nature & Deities – Akan gods govern elements of nature, such as rivers, mountains, and the sky, signifying the deep connection between spirituality and the environment.

- Symbols & Proverbs – Akan mythology is rich with symbols and proverbs, which serve as guiding principles in daily life. The Adinkra symbols, a system of ideographic motifs, encapsulate moral lessons, spiritual beliefs, and philosophical concepts. One of the most revered symbols is “Gye Nyame,” meaning “Except for God,” which signifies Nyame’s omnipotence. Akan proverbs, often drawn from myths and folktales, emphasize wisdom, communal values, and ethical conduct. These sayings, passed down through generations, reinforce the Akan worldview, linking their mythology to social and moral teachings.

Below is a breakdown of major deities and figures within Akan mythology.

Major Deities

Nyame (Supreme Sky God)

- Origin: West African Mythology

- Classification: Supreme Deity

- Region: Ghana

- Associated With: Sky, Creation, Omniscience

- Other Names: Onyame, Nyankopon, Odomankoma

Overview

Nyame is the supreme sky deity and creator god of Akan mythology. He is regarded as the one who knows and sees everything, governing the universe and overseeing all other gods, spirits, and mortal beings. He forms a triad with Nyankopon and Odomankoma, representing different aspects of the cosmos.

Attributes

- All-knowing and omnipotent – Oversees cosmic order.

- Symbol of the Sun – The sun represents his watchful gaze over the world.

- Creator of Life – Formed the universe alongside his consort, Asase Yaa.

Role in Mythology

- Nyame is the originator of the Abosom (lesser gods) and the guardian of moral justice.

- He entrusted earthly affairs to other deities but maintains supreme control over fate and destiny.

Modern Influence

- The Adinkra symbol “Gye Nyame” represents Nyame’s omnipotence, often seen in Ghanaian art and clothing.

- His significance persists in modern Akan spirituality, where prayers are often directed to him before invoking lesser deities.

Asase Yaa (Earth Goddess & Fertility Deity)

- Origin: Akan & Ashanti Mythology

- Classification: Goddess

- Region: Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire

- Associated With: Earth, Fertility, Harvest, Peace, Truth

- Other Names: Asase Afua, Aberewaa

Overview

Asase Yaa, also called Old Mother Earth, is the goddess of fertility, land, and agriculture. She is both a nurturer and a judge, associated with truth, peace, and life-giving forces.

Attributes

- Two Forms:

- Asase Yaa – A wise elder who governs barren lands.

- Asase Afua – A youthful, vibrant aspect overseeing fertile lands.

- Embodiment of Justice – Oaths are sworn upon her name to ensure honesty.

- Cradle of Ancestors – She welcomes souls back into the earth upon death.

Role in Mythology

- Considered second only to Nyame, she governs the land’s fertility.

- She is the mother of Bia and Tano, and in some myths, Anansi.

Modern Influence

- Farmers still perform rituals to honor her before planting.

- The concept of Earth Day celebrations in Ghana aligns with her worship.

Tano (God of the Tano River)

- Origin: West African Mythology

- Classification: River Deity

- Region: Ghana

- Associated With: Water, Fertility, Agriculture, Justice

- Other Names: Tano Kwesi, Tano Nyame

Overview

Tano is the spirit of the Tano River, one of Ghana’s most sacred waterways. He is a guardian of justice, agriculture, and the life-giving force of water.

Attributes

- Protector of Nature – Ensures water purity and fertility.

- Symbol of Justice – Offenders were historically tried at the river.

- Transformative Abilities – Can manifest as a wise elder or aquatic spirit.

Role in Mythology

- Considered a son of Nyame and brother to Asase Yaa and Bia.

- His wrath results in floods and poor harvests if disrespected.

Modern Influence

- Worship practices remain among river communities in Ghana.

- His environmental symbolism influences water conservation efforts.

Anansi (The Trickster Spider God)

- Origin: West African & Caribbean Mythology

- Classification: Trickster Deity

- Region: Ghana, Caribbean, African Diaspora

- Associated With: Trickery, Wisdom, Storytelling

- Other Names: Kwaku Anansi, Aunt Nancy (U.S.), Kompa Nanzi (Caribbean)

Overview

Anansi is one of the most famous African deities, known for his wit, cunning, and storytelling abilities. He represents survival through intelligence rather than brute strength.

Attributes

- Shapeshifter – Can take the form of a spider or a man.

- Moral Trickster – Teaches life lessons through deception.

- Patron of Storytelling – His tales form the backbone of Akan oral traditions.

Role in Mythology

- Often outwits powerful beings using intelligence and humor.

- Represents resistance and resilience, particularly among enslaved Africans.

Modern Influence

- His tales remain widespread in Ghana, the Caribbean, and the U.S.

- Appears in books, films, and even comics (e.g., Neil Gaiman’s Anansi Boys).

Ntikuma (Son of Anansi & Clever Hero)

- Origin: Akan Mythology

- Classification: Mortal Trickster

- Region: Ghana

- Associated With: Intelligence, Storytelling, Morality

Overview

Ntikuma is Anansi’s youngest son, inheriting his father’s cleverness. However, unlike Anansi, Ntikuma often acts as a moral counterbalance, outsmarting his trickster father.

Attributes

- Human-like – Unlike Anansi, he is portrayed as a young boy.

- Symbol of Justice – Uses intelligence to right wrongs.

Modern Influence

- His stories serve as moral lessons in Akan culture.

- Often appears in folktales and literature as a problem solver.

References

- Abrahams, Roger D. African Folktales: Traditional Stories of the Black World. New York: Pantheon Books, 1983.

- Awuah-Nyamekye, Samuel. Managing the Environmental Crisis in Ghana: The Role of African Traditional Religion and Culture with Special Reference to the Akan. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014.

- Barber, Karin. African Popular Culture. James Currey Publishers, 1991.

- Courlander, Harold. A Treasury of African Folklore. Marlowe & Company, 1995.

- Danquah, Joseph B. The Akan Doctrine of God. London: Lutterworth Press, 1968.

- Herskovits, Melville J. Myth and Folk Tales of the African World. 1946.

- Mbiti, John S. African Religions & Philosophy. London: Heinemann, 1990.

- McLeod, Malcolm D. The Asante. London: British Museum Publications, 1981.

- Pobee, John S. Religion and Social Change in Africa: A Study of the Akan Religion and Christianity. 1976.

- Rattray, R. S. Religion and Art in Ashanti. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1923.

- Rosenberg, Donna. World Mythology: An Anthology of Great Myths and Epics. 1992.

- Wynter, Sylvia. Anancy in the Great House: Ways of Reading West Indian Fiction. 1970.

- The Akan of Ghana: Aspects of Past and Present Practices by by Kofi Ayim (Author)

- African Religion Defined: A Systematic Study of Ancestor Worship Among the Akan by Anthony Ephirim-Donkor

- Speaking for the Chief: Okyeame and the Politics of Akan Royal Oratory (African Systems of Thought) by Kwesi Yankah

- The Akan Folktales of Kwaku Anansi: Tales of Wisdom, Cunning, and Trickery by Eric Awiti Sraha

- AKAN-ASHANTI FOLKTALES ( REVISED & ANNOTATED): (A COLLECTION OF 75 ASHANTI FOLKTALES) by R. S. RATTRAY & P. SARFO-ADU

Leave a Reply